Published

Tue, Mar 22, 2011, 12:30

- We use this Friday's Dynamic Range Day day to look at the root of this ongoing production issue.

On March 25th, the world will celebrate Dynamic Range Day. Admittedly, my parents won't; I'm not sure my children will learn about it in class and, all jokes aside, there's a decent chance that some artists and mastering engineers will also ignore it. This week, I'd like to explore why it would be great if we all paid the subject of dynamics and their sad decline from so much recorded music due heed.

As you probably know, the movement to consciously restore dynamics back into recordings is that, systematically over the past few years, they've been removed in the recordings we hear and buy. Anyone reading this is likely to be familiar with the concept of compression, whose job it is to bring the dynamic range of any sound down. In other words, it forces the loudest bits of a sound closer to the quietest bits and vice versa.

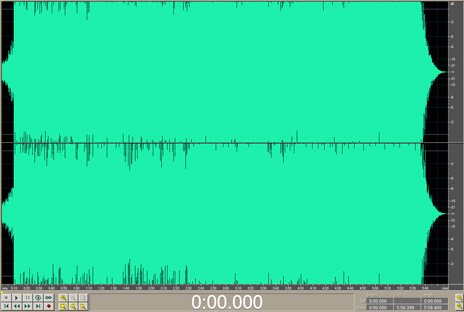

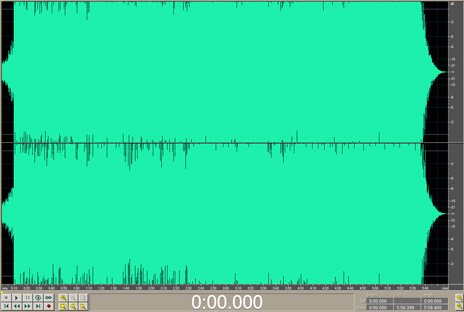

The problem with compression is that it evens out volume. When you combine heavy gain reduction (the amount of volume scooped out of a sound) with output gain (the amount of volume added to compensate), you end up with so much "even volume" that the concept of "volume change" ceases to exist. As compression is such a popular and efficient weapon in the modern studio, it's not uncommon to find its use on the majority of individual sounds in any mix. Combine these with an extra compressor in the output master channel, followed by a loudness maximiser, and it's easy to see how dynamic change might find itself out in the cold.

Loudness maximisers are tools usually reserved exclusively for the mastering stage of a project and their job is two-fold. Firstly, they prevent signals from exceeding digital maximum, which is set at 0dB. Secondly, they allow you to add volume to any signals which fall short of this ceiling so that any remaining dynamic range which has survived the mixing stage can be hyped, pumped and super-charged. The analogy of a pressure cooker is perfect here—imagine a lid which doesn't let steam escape and a roaring fire beneath to ensure that everything in the pan is desperately leaping toward the surface... something's gotta give, surely?

Well yes. The thing that gives is one of music's fundamental ingredients. Musical instruments, whether acoustic or electronic, can control three things—pitch, tone and volume. That's it. Pitches can range from roughly 20Hz to 20kHz before we fail to hear them at either extreme, while descriptions of tone bring out our artistic side; dark, warm, piercing, pure, full, rich. Volume, from silence to speaker-busting, chest-constricting maximum is the third piece in this jigsaw trinity and to throw it away by setting everything, by default, at maximum is to remove light and shade.

When you think about it, it's remarkable we ever decided removal of dynamic range seemed sensible. After all, you can only experience loud if you know what quiet is. We might as well have buttons in our mixers or on our amplifiers which are simply labeled "off" and "loud"; any concept of a smooth fader or dial with intermediate points between 0 and 10 is pointless. Or think about it this way—imagine if all music was deliberately restricted in pitch, one of the other musical keystones. The call would come: "All music must be in G major" and we'd rebel, instantly.

So, what it is about dynamic range that we're so willing to discard? The simple fact that loud is impressive. Be honest, when you've finished a mix you like and a friend pops round to hear it, do you turn it up or down? Equally, when work isn't quite going as well as you'd hoped and your track's lacking inspiration, do you turn it up or down to convince yourself it's still "got something"? Up, up, up. Always up. And it's this naturally competitive spirit in all of us which lead to the well-documented loudness wars which have consumed artists and their mastering engineers alike. One record is mastered loudly, someone else doesn't want theirs to sound quiet by comparison, so they slam theirs even harder at the mix stage.

The alternative is that we leave listening volume in the hands of the audience it was intended for—the listener. If you want it loud, turn it up, but if you also want the pin-drop drama of deliberately quieter moments, these can be yours too. Radio broadcasting naturally compresses output signals anyway, so if you're mastering with concern that you must compete with other records, this needn't worry you. In fact, your record might well sound better on radio having not been squashed twice. So, head over to dynamicrangeday.com if you want to join the growing faithful who wish to reclaim dynamics as an essential mix ingredient. For one day, at least.

Well yes. The thing that gives is one of music's fundamental ingredients. Musical instruments, whether acoustic or electronic, can control three things—pitch, tone and volume. That's it. Pitches can range from roughly 20Hz to 20kHz before we fail to hear them at either extreme, while descriptions of tone bring out our artistic side; dark, warm, piercing, pure, full, rich. Volume, from silence to speaker-busting, chest-constricting maximum is the third piece in this jigsaw trinity and to throw it away by setting everything, by default, at maximum is to remove light and shade.

When you think about it, it's remarkable we ever decided removal of dynamic range seemed sensible. After all, you can only experience loud if you know what quiet is. We might as well have buttons in our mixers or on our amplifiers which are simply labeled "off" and "loud"; any concept of a smooth fader or dial with intermediate points between 0 and 10 is pointless. Or think about it this way—imagine if all music was deliberately restricted in pitch, one of the other musical keystones. The call would come: "All music must be in G major" and we'd rebel, instantly.

So, what it is about dynamic range that we're so willing to discard? The simple fact that loud is impressive. Be honest, when you've finished a mix you like and a friend pops round to hear it, do you turn it up or down? Equally, when work isn't quite going as well as you'd hoped and your track's lacking inspiration, do you turn it up or down to convince yourself it's still "got something"? Up, up, up. Always up. And it's this naturally competitive spirit in all of us which lead to the well-documented loudness wars which have consumed artists and their mastering engineers alike. One record is mastered loudly, someone else doesn't want theirs to sound quiet by comparison, so they slam theirs even harder at the mix stage.

The alternative is that we leave listening volume in the hands of the audience it was intended for—the listener. If you want it loud, turn it up, but if you also want the pin-drop drama of deliberately quieter moments, these can be yours too. Radio broadcasting naturally compresses output signals anyway, so if you're mastering with concern that you must compete with other records, this needn't worry you. In fact, your record might well sound better on radio having not been squashed twice. So, head over to dynamicrangeday.com if you want to join the growing faithful who wish to reclaim dynamics as an essential mix ingredient. For one day, at least.

Well yes. The thing that gives is one of music's fundamental ingredients. Musical instruments, whether acoustic or electronic, can control three things—pitch, tone and volume. That's it. Pitches can range from roughly 20Hz to 20kHz before we fail to hear them at either extreme, while descriptions of tone bring out our artistic side; dark, warm, piercing, pure, full, rich. Volume, from silence to speaker-busting, chest-constricting maximum is the third piece in this jigsaw trinity and to throw it away by setting everything, by default, at maximum is to remove light and shade.

When you think about it, it's remarkable we ever decided removal of dynamic range seemed sensible. After all, you can only experience loud if you know what quiet is. We might as well have buttons in our mixers or on our amplifiers which are simply labeled "off" and "loud"; any concept of a smooth fader or dial with intermediate points between 0 and 10 is pointless. Or think about it this way—imagine if all music was deliberately restricted in pitch, one of the other musical keystones. The call would come: "All music must be in G major" and we'd rebel, instantly.

So, what it is about dynamic range that we're so willing to discard? The simple fact that loud is impressive. Be honest, when you've finished a mix you like and a friend pops round to hear it, do you turn it up or down? Equally, when work isn't quite going as well as you'd hoped and your track's lacking inspiration, do you turn it up or down to convince yourself it's still "got something"? Up, up, up. Always up. And it's this naturally competitive spirit in all of us which lead to the well-documented loudness wars which have consumed artists and their mastering engineers alike. One record is mastered loudly, someone else doesn't want theirs to sound quiet by comparison, so they slam theirs even harder at the mix stage.

The alternative is that we leave listening volume in the hands of the audience it was intended for—the listener. If you want it loud, turn it up, but if you also want the pin-drop drama of deliberately quieter moments, these can be yours too. Radio broadcasting naturally compresses output signals anyway, so if you're mastering with concern that you must compete with other records, this needn't worry you. In fact, your record might well sound better on radio having not been squashed twice. So, head over to dynamicrangeday.com if you want to join the growing faithful who wish to reclaim dynamics as an essential mix ingredient. For one day, at least.

Well yes. The thing that gives is one of music's fundamental ingredients. Musical instruments, whether acoustic or electronic, can control three things—pitch, tone and volume. That's it. Pitches can range from roughly 20Hz to 20kHz before we fail to hear them at either extreme, while descriptions of tone bring out our artistic side; dark, warm, piercing, pure, full, rich. Volume, from silence to speaker-busting, chest-constricting maximum is the third piece in this jigsaw trinity and to throw it away by setting everything, by default, at maximum is to remove light and shade.

When you think about it, it's remarkable we ever decided removal of dynamic range seemed sensible. After all, you can only experience loud if you know what quiet is. We might as well have buttons in our mixers or on our amplifiers which are simply labeled "off" and "loud"; any concept of a smooth fader or dial with intermediate points between 0 and 10 is pointless. Or think about it this way—imagine if all music was deliberately restricted in pitch, one of the other musical keystones. The call would come: "All music must be in G major" and we'd rebel, instantly.

So, what it is about dynamic range that we're so willing to discard? The simple fact that loud is impressive. Be honest, when you've finished a mix you like and a friend pops round to hear it, do you turn it up or down? Equally, when work isn't quite going as well as you'd hoped and your track's lacking inspiration, do you turn it up or down to convince yourself it's still "got something"? Up, up, up. Always up. And it's this naturally competitive spirit in all of us which lead to the well-documented loudness wars which have consumed artists and their mastering engineers alike. One record is mastered loudly, someone else doesn't want theirs to sound quiet by comparison, so they slam theirs even harder at the mix stage.

The alternative is that we leave listening volume in the hands of the audience it was intended for—the listener. If you want it loud, turn it up, but if you also want the pin-drop drama of deliberately quieter moments, these can be yours too. Radio broadcasting naturally compresses output signals anyway, so if you're mastering with concern that you must compete with other records, this needn't worry you. In fact, your record might well sound better on radio having not been squashed twice. So, head over to dynamicrangeday.com if you want to join the growing faithful who wish to reclaim dynamics as an essential mix ingredient. For one day, at least.